How to Clean & Sanitize Your iPhone & Other Apple Devices

I rarely write a tip that will impact people's health, but learning how to clean and sanitize your Apple devices, including your iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, AirPods, Mac, and even Apple TV remote, is part of how to prevent coronavirus. Some of these items are on our person nearly all the time, especially the iPhone, Apple Watch, and AirPods, and therefore have more bacteria and viruses on them than the average toilet seat. Apple has recently changed their cleaning guidelines, so let's go over how to sanitize your cellphone, tablet, earbuds, smartwatch, and other Apple devices.

Related: 5 Apps That Move Medical Research Forward

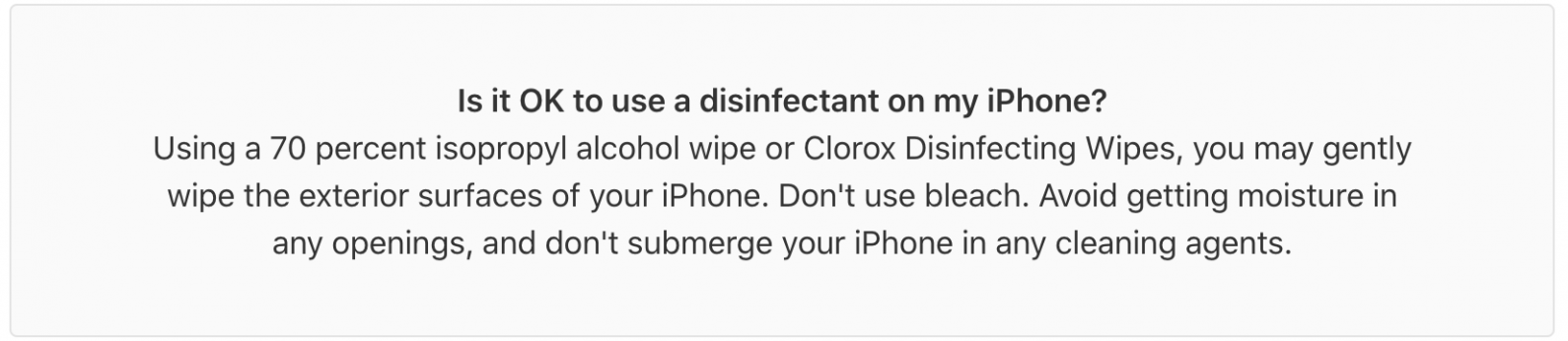

Apple previously warned customers not to use ANY cleaning products whatsoever, to prevent damage to their oleophobic finish. In light of the current situation, Apple has updated its cleaning guidelines with the following announcement, saying it is safe to use a 70 percent isopropyl alcohol wipe, such as a Clorox Wipe.

How to Sanitize Your iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, AirPods & Other Apple Tech

- Remove your device's case.

- Turn off your phone or tablet and unplug any attached cables.

- Throroughly clean your device with a 70 percent isopropyl alcohol wipe, such as a Clorox Wipe.

- Avoid excessive wiping and rubbing; this may damage finishes.

- Try not to get moisture in any openings, ports, or speaker or microphone meshes.

- Do not use any other cleaning products, sprays, abrasives, or compressed air.

If you're cleaning your Apple Watch, keep in mind that Clorox wipes may damage the band. As in the previous steps, be sure not to get moisture from the antimicrobial wipe into any openings in your device. For those of you who are concerned about your iPhone or iPad's finish, use a case and screen protector and leave them on, then use your Clorox wipes to sanitize them thoroughly.

Every day, we send useful tips with screenshots and step-by-step instructions to over 600,000 subscribers for free. You'll be surprised what your Apple devices can really do.

Leanne Hays

Leanne Hays has over a dozen years of experience writing for online publications. As a Feature Writer for iPhone Life, she has authored hundreds of how-to, Apple news, and gear review articles, as well as a comprehensive Photos App guide. Leanne holds degrees in education and science and loves troubleshooting and repair. This combination makes her a perfect fit as manager of our Ask an Expert service, which helps iPhone Life Insiders with Apple hardware and software issues.

In off-work hours, Leanne is a mother of two, homesteader, audiobook fanatic, musician, and learning enthusiast.

Amy Spitzfaden Both

Amy Spitzfaden Both

Rhett Intriago

Rhett Intriago

Rachel Needell

Rachel Needell

Leanne Hays

Leanne Hays

Olena Kagui

Olena Kagui

Ashleigh Page

Ashleigh Page