Privacy in the Public Age: Apple Claims to Keep You Safe, but Can It Really?

Related: All the Ways Apple Is Beefing Up Security & Privacy for Its Users

Ours is the public age—the age of workout-sharing, of food selfies, of teens using Instagram or TikTok to broadcast every daily experience. Perhaps it’s no surprise that privacy is evaporating. But those are all individual choices, moments in life a person chose to share. A key feature of a right is the option to waive it: the right to privacy can be defined as the right to choose which parts of your life to make public and which to keep from the eyes of others. Oversharing on Facebook may be a social faux pas, but Apple cannot stop you. Law enforcement agencies, internet stalkers, and advertising companies all have uses for that public data, but nobody, including Apple, can protect you from your own willful broadcast of details of your life.

In this public age, your activity is also tracked by machines. Machines record everything you do, from websites you visit to what you write privately in your digital journals and notes. If you use diet, exercise, and health programs, then they track what you eat, how far you can run, and when you last spent intimate time with a partner. What can the companies who make those machines do with all that data? This brings us to the first major annoyance of the public age: advertising.

Browser Tracking & Apple

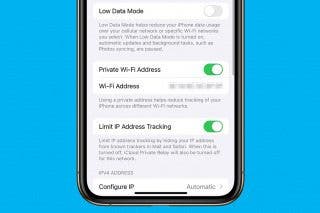

Here is the heart of Apple’s promise: the information you entrust to your iPhone stays on your iPhone, and the information you entrust to iCloud stays inside your iCloud. Apple promises not to transmit that data to advertising partners. It doesn’t store it outside your account, and it can’t access it for its own purposes inside your account. It’s yours. Google, Facebook, and Amazon make no such promises.

Google and Facebook make their money by matching advertisements to people who would like to click on them. If you think of it as a business selling widgets, the widgets Google and Facebook sell are packages containing user patterns and preferences, and they sell those packages to advertisers. Ever wonder how ads on the internet seem to know what you’re thinking? The machine-learning algorithms Google and Facebook use to understand your preferences and patterns can be frighteningly prescient.

iPhone users may be insulated from this kind of preference sleuthing, but only if they never use Google or Facebook or their associated apps and services. It doesn’t matter if you’re using Google search on a virus-ridden PC running Windows 95 or on a pristine iPhone. In either case, Google will know what you searched for, what you clicked on, and how long you spent reading it. That said, iPhone users may protect themselves from this kind of big-data harvesting in some important ways.

For example, Apple Maps doesn’t keep records of your location the way that Google Maps does. Apple’s Safari web browser submits less information about you and your computer to Google than does Google’s Chrome browser. But, on the other hand, queries typed into Safari use Google search by default, so Safari users usually end up sending data to Google anyway. According to a Goldman Sachs’ analyst, Apple receives billions of dollars each year from Google for the privilege of remaining the default search engine in Safari. Phrased another way, Apple essentially sells your search traffic to Google, which then gets to harvest your web usage data.

You can opt out easily enough by changing Safari’s default search engine to one that doesn’t track you, like startpage.com. But, if Apple wants to wag a finger at Google about privacy issues, it might consider changing Safari’s default search engine to something other than Google.

Advertising profiles and user patterns may seem reasonably benign. Still, most of us can’t shake the nagging fear that someone nefarious could gain access to the trove of information about us that is generated and stored by Google or Facebook. What kind of bad actors are out there, what kind of data do they want, and how are they most likely to gain that data?

iPhone Malware & Viruses

Alas, iPhones and Mac computers are not immune to viruses, nor are they immune to malware. The 2020 State of Malware Report by Malwarebytes, a virus and threat detection company, found that in 2019, malicious software infections on Mac computers outpaced those on Windows. The seriousness of those Mac infections is still somewhat less than what a Windows machine might experience. The most common Mac threats, such as those called NewTab and Genieo, hijack your internet searches and direct them to sponsored pages to generate advertising revenue for the malware’s authors. Windows computers, on the other hand, are much more likely than Macs to be hit by ransomware or other malware that thoroughly trashes the machine. That said, more and more users are abandoning system-specific software and turning to browser and cloud-based software instead. For example, users are giving up on Microsoft Word, which runs on your computer, in favor of Google Docs, which runs in a web browser and is stored in the cloud via Google Drive. Because you can use these browser-based programs on a Mac or a PC equally, they’ve become an attractive target for hackers and scammers. Why choose between writing malware to target Mac or Windows, when you could hit both? So yes, Apple computers are safer, but that edge is slipping, and it is no edge at all if you use third-party systems.

The same report from Malwarebytes noted that while threats exist for iPhones, there is no way to know what they are or how likely they are to hit you. This is because Apple doesn’t allow iOS apps to scan iOS devices on the level necessary to detect malicious behavior. Therefore, companies specializing in protecting consumers from malware can’t help very well on an iPhone. Malicious apps exist, and we know this because sometimes Apple announces that it’s removed some from the App Store. Apple maintains sole responsibility for finding and removing them. So, is an iPhone safer than an Android? Yes, probably. But the recommendation is the same for both kinds of phones: always check up on an app before you install it.

Identity Theft & Fraud

Identity theft is the boogeyman of the public age, the predatory dark figure, lurking in the shadows of the internet, lapping up social media data, and using it to ruin lives. This boogeyman is real enough. In 2019, more than two hundred forty thousand people reported a fraudulent credit card account had been opened using their identity, according to the Federal Trade Commission’s Consumer Sentinel Network Data Book for 2019. That number is expected to rise in 2020 and beyond. While credit card fraud is the most common kind of identity theft, it isn’t the worst kind. To open a credit card account, a scammer only needs your social security number, your yearly income, and your street address. Stolen personal information can also allow scammers to take out student loans, sign leases, and even, rarely, to create false IDs, but these require significantly more access to your data.

Identity thieves usually obtain what they need to know about you by one of a few common scams. In no particular order, they include first phone calls where they either trick you or intimidate you into giving up your social security number—impersonating the IRS, banks, or debt collectors are all common tactics. Second, are dumpster divers who find discarded documents. Third, by drag-net style, are scammers who send emails to millions of accounts, hoping to lure the unwary into handing over information. Owning an iPhone will protect you from none of these scams because, in these situations, the victim is the one who surrenders their information. They either throw it away, or hand it out in direct communication with a scammer. Apple isn’t involved.

Another way a scammer might get ahold of your social security number is by gaining access to online accounts where you store personal records, like Notes, Files, or Microsoft Word’s cloud services. One common way they achieve that access is by running scripts to try common passwords with every account they can find. You might be surprised how many people set their password to something like 123456789. Grab a list of email addresses from an advertising agency, then enter them along with that password on any given cloud service website, and you’re sure to get into somebody’s account. Here, at last, Apple can help with its iCloud Keychain password manager and multi-factor authentication. Apple users who correctly employ those services will be warned if their password is common or easy to guess and will get a pop-up notification on their phone when anyone tries to get into their iCloud account on an unrecognized device. It’s only fair to mention that Google offers a similar service with Chrome’s password manager. Also, multi-factor authentication is now available from most major cloud services. So yes, Apple will protect you from fraud, but so will Google or Microsoft. Apple’s protection is better, but you still have to actually use it.

If owning an iPhone means you give in to Apple’s efforts to convince you to use two-factor authentication and employ strong passwords, then you will certainly be safer. Apple’s advertising of privacy and security features might be seen as an important public service. They raise awareness about the problems and about the tools to help solve them. Maybe that ad wasn’t so dystopian after all.

For quick, easy lessons on how to use your iPhone and other Apple devices, subscribe to our free Tip of the Day.

Cullen Thomas

Cullen Thomas is a senior instructor at iPhone Life. For ten years as faculty at Maharishi University, Cullen taught subjects ranging from camera and audio hardware to game design. Cullen applies a passion for gadgetry to answer questions about iPhones, iPads, Macs, and Apple cloud services; to teach live classes; and to specialize in the privacy and security aspects of the Apple ecosystem. Cullen has dual degrees in Media & Communications and Literature, and a Masters degree from the David Lynch Graduate School of Cinematic Arts.

Offline, Cullen designs videogames with Thought Spike Games, writes fiction, and studies new nerdery.

Mastodon: @CullenWritesTech@infosec.exchange

Email: cullen@iphonelife.com

Signal: +1-512-814-5526

Rachel Needell

Rachel Needell

Olena Kagui

Olena Kagui

Leanne Hays

Leanne Hays

Devala Rees

Devala Rees

August Garry

August Garry

Amy Spitzfaden Both

Amy Spitzfaden Both

Rhett Intriago

Rhett Intriago